The Research

How do families of various backgrounds perceive and experience race and racism? To answer this, our friends at Nickelodeon Consumer Insights surveyed more than 15,000 families in 2019 and 2020, representing a broad cross-section of America and its varied social and political demography. Then, to better understand how families have discussions about race and racism, two qualitative follow-up studies were conducted. In the first, Black and White parent-child pairs discussed “racist scenarios” while a researcher watched. In the second, Black, Asian, Hispanic, and White families discussed scenarios to allow the researchers to understand a larger demographic.

Core Findings: "Let's Talk About Race & Racism"

Kids are Often Ready to Talk Before Parents Start Talking.

Children start noticing race during infancy.

Previous research has shown that children start noticing race as babies. Between 6 and 12 months, babies begin to show a preference for members of their own racial groups (source). By 9 months old, infants looked longer at own‐race faces paired with happy music than at own‐race faces paired with sad music (source). From their earliest age, children are picking up on status from the culture around them (source).

But parents often think kids aren't ready to talk about race and racism yet.

Previous research has demonstrated that U.S. adults underestimate kids' ability to understand and talk about race. Grown-ups say children develop the capacity to process and understand race at around age 5, but research shows most are capable of understanding and talking about race as toddlers. This misjudging of children's capacity has an impact on when parents start talking about race/racism with their children (source).

Parents of all races say they feel unprepared to talk about race and racism.

When asked to rate how prepared they felt to discuss stories of racism with their kids on a scale of 1-5, Black and White parents reported feeling equally unprepared, with an average rating for both families of 2.4 out of 5.

Here are some examples of how parents in the "Let's Talk about Race and Racism" research talked about it:

A Black mother: “Even though she’s very smart, I hadn't figured out a way to explain to her for her six-year-old self to explain it and not be upset about it, and not be emotional about it.”

A White mother: "I don't want to break his perfect little world. You know what I mean?"

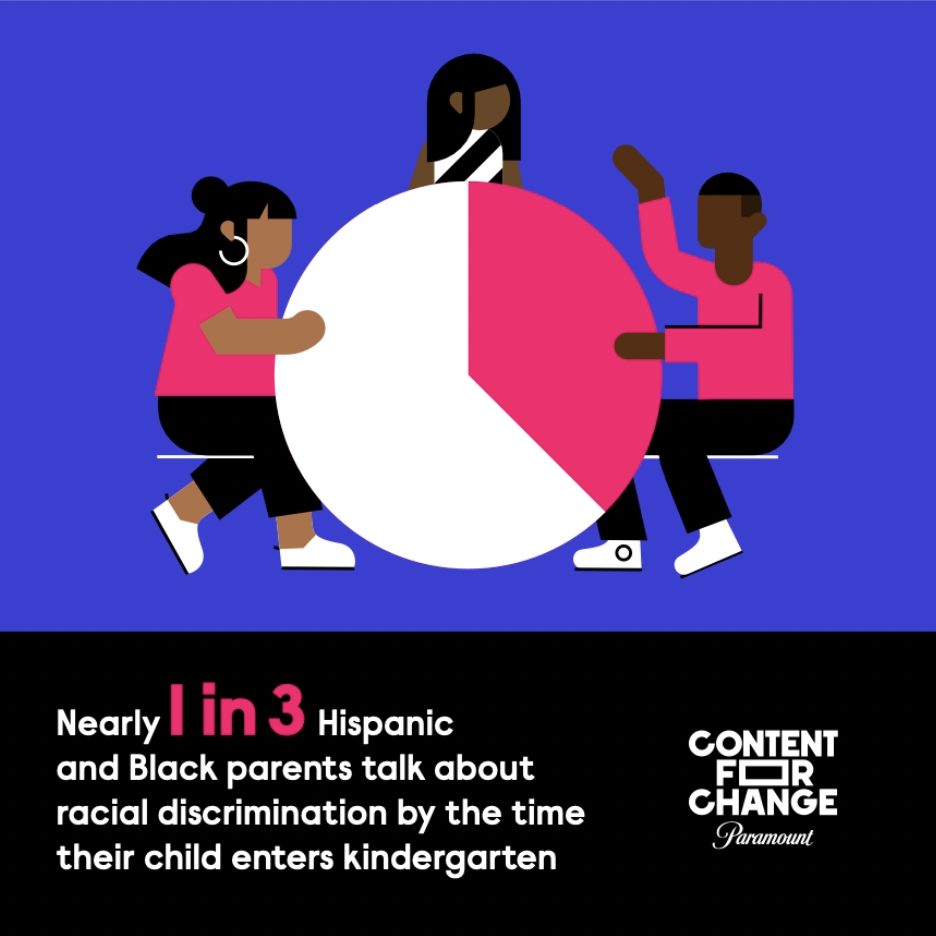

While all parents reported feeling unprepared, parents of color are talking with kids earlier.

By the time their child is 10 years old, the vast majority of Black (82%), Hispanic (80%), and Asian (71%) parents have conversations with their kids about the discrimination they may face (compared to only 37% of White families).

Nearly one out of three Hispanic and Black parents are talking about racial discrimination by the time their child enters kindergarten.

These conversations are bred out of necessity. Asian families say they are talking to their kids about dealing with or avoiding harassment – including increased harassment resulting from misperceptions around the Coronavirus. Hispanic parents are talking to their kids about the use of Spanish outside the home (whether speaking or playing music).

Perceptions and Experiences of Race and Racism Differ Across Races.

Black children see race as key to identity. White children do not.

Race is an extremely large contributor to Black children’s self-identity, a medium contributor to Hispanic and Asian children, but doesn’t even rank for White children. Similarly, among Black parents, race is believed to be a major factor in how their families are treated. Hispanic and Asian parents see race as a medium factor, while it does not play a role among White parents.

Black parents notice more anti-Black bias.

Parents of all races agreed Black people face the most discrimination, however there were large discrepancies in the perceptions of how much discrimination Black people face.

- 80% of Black parents reported facing a lot of discrimination

- The percentage of White parents who think Black families face discrimination is half that — just 41%.

It’s not just parents who understand discrimination. Children, too, are aware of race treatment disparities. Kids were asked what their lives would be like as a different race, and ¾ of Black children believe their lives would be easier if they were White. Meanwhile, only ⅓ of White children believe their lives would be harder if they were Black, meaning that ⅔ of White children think their lives would be the same or easier if they were Black. This finding suggests that most White children may not be aware of the discrimination Black people face or the heavy impact that it has on their lives.

Stereotypes start early.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (2020) reports that children as young as two years old can internalize racial bias. A study by Northwestern University showed negative bias towards Black boys at just four years old (Perszyk et al., 2019).

In "Let's Talk About Race & Racism," when 3- and 4-year-old children worked through the illustrated "similarities and differences" activity, parents were taken aback by their children’s preferences for playmates that looked like them.

Here is an exchange between a White mother and her 4-year-old White son:

Mother: If you were at the park with all these kids, who would you want to play with? [son points to a White kid on the steps]

Mother: How come?

Child: Because he has the same skin as me.

A similar exchange occurred between a Black mother and her 3-year-old Black son.

Mother: Why would you want to play with him?

Child: Because he looks like me, almost.

Even though having preferences to those similar to you is developmentally expected, it highlights the importance of early conversations around celebrating differences instead of avoiding them, and finding similarities between people that are beyond the surface.

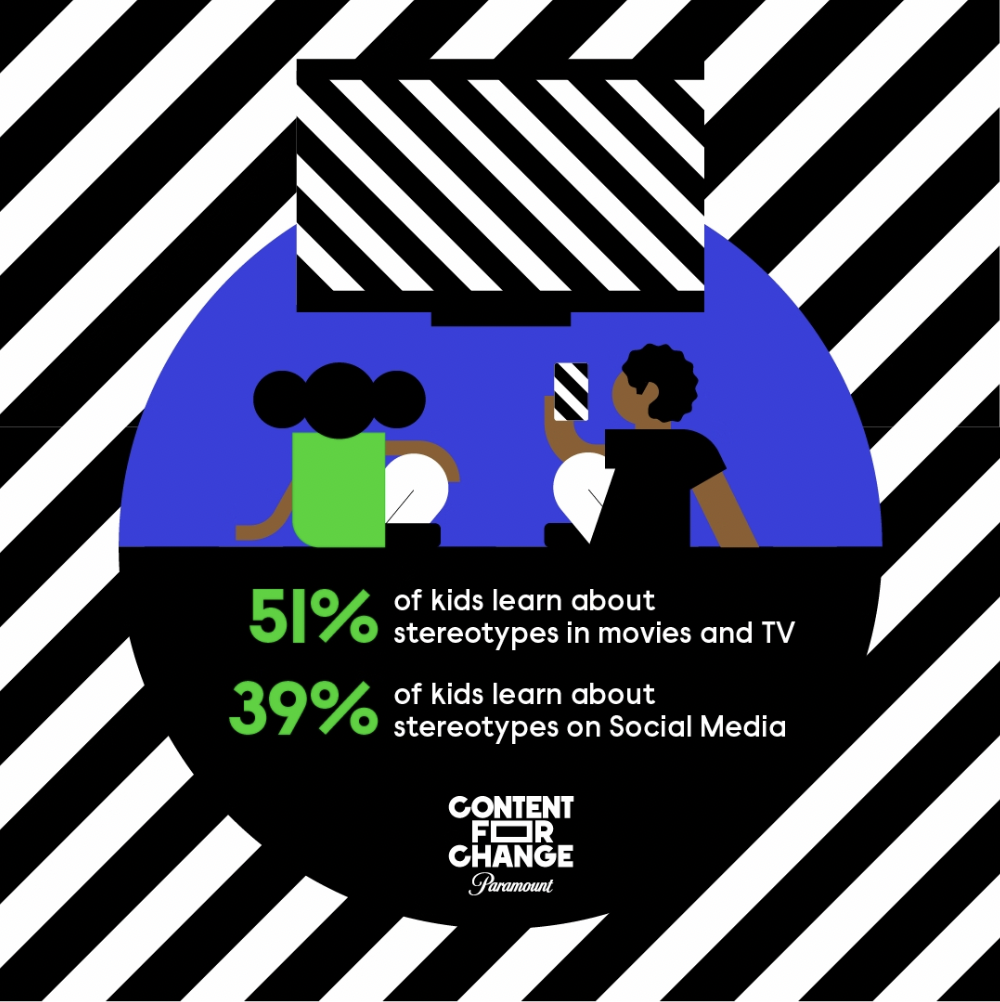

School and media are sources of stereotypes.

The top three places kids reported hearing stereotypes are:

- At school (61%)

- In movies and on TV (51%)

- On social media (39%)

Kids of color are more likely than White kids to feel that their race/ethnicity is not well-portrayed in movies and on television: 55% of Black kids said their race was not portrayed well, compared to 45% of Hispanic kids, 40% of Asian kids, and 30% of White kids.

In the "Let's Talk About Race & Racism Research," a young Asian boy pointed out that most princesses he has seen have light skin, not dark. One young Black girl told her mother she thought robbers were Black because that’s all she’s seen on TV shows and in movies.

Kids of color don't feel they are well portrayed on screen.

Researchers asked kids whether or not they think their race/ethnicity is well portrayed in television and movies.

Forty percent of Asian kids, 45% of Hispanic kids and 55% of Black kids did not think they are well portrayed in media. (Only 30% of White kids did not think their race was well portrayed in media.)

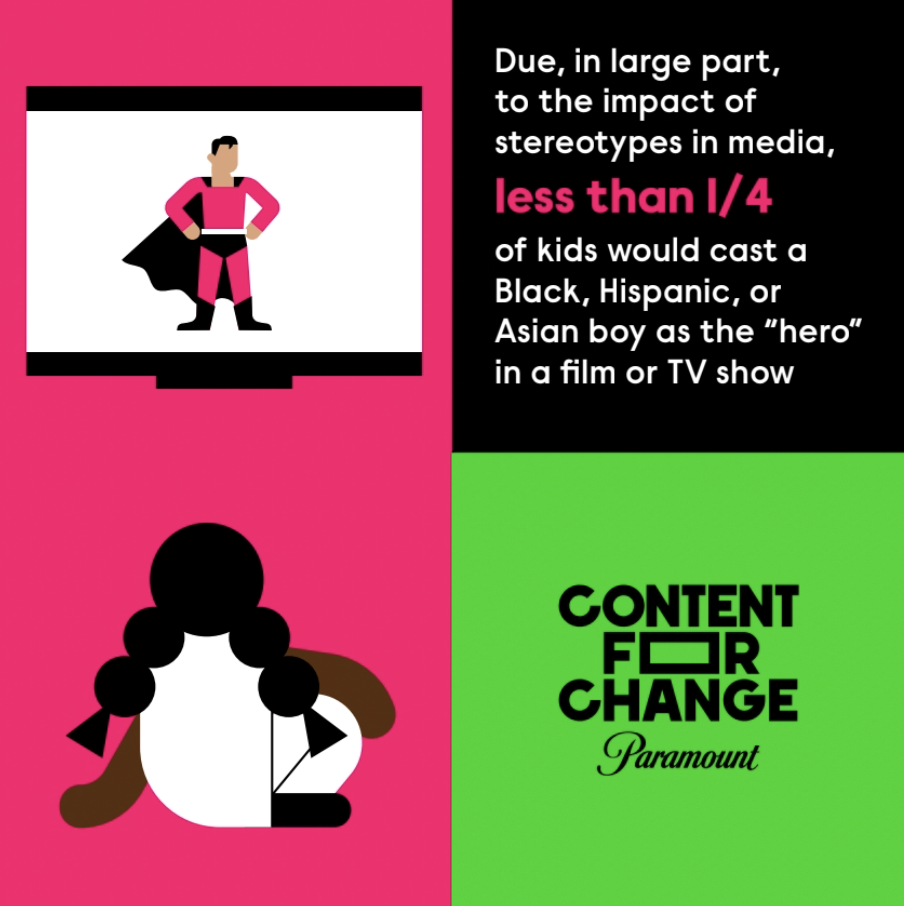

Kids notice and internalize media stereotypes.

When kids were asked to reflect on stereotypes in films and TV shows, 52% of kids would cast a white boy as the “hero,” while only 19% of kids would cast a Black boy in the role, and just 12% picking Hispanic and Asian boys. It’s time for a reality check on the pervasiveness of character tropes based on race, ethnicity, and gender that children have been indirectly taught over the years.

It's important — especially to kids of color — to see themselves represented on screen.

According to the research, about half of Hispanic and Asian kids and nearly three-quarters of Black kids think it’s important to see their own race/ethnicity on screen. (Just one-third of White children feel it is important.)

Families of different races had different responses to racist scenarios.

Advisors helped to construct scenarios to share with parent-child pairs during research.

All eight conversation prompts were based on real scenarios, and created by a team of BIPOC advisors and researchers. For example, in one, a White girl does not want to invite a Black girl to her party saying she doesn't like Black people. In another, a security guard in a store is following a Black mother and daughter but not a White mother and daughter, and only checks the bags of the Black family. Immediately following the parent-child conversation, the moderator had an in depth interview with the parent.

Families of different races use different words to discuss race and racism.

When discussing the situations in the prompts provided by the researchers, all families used words such as unfair vs. fair, and right vs. wrong, but Black families were far more likely than White families to use the terms racist and racism. Specifically, Black kids were four times as likely to use the terms racist and racism, and Black parents were three times as likely. White families tended to describe the situations with words such as good vs. bad, mean, not nice, and rude.

Black families were more likely than White families to use emotion-based words such as angry, mad, sad, and upset.

Using color-evasive language like “we don’t see color” can be problematic for several reasons. It creates a taboo around race and differences, rather than celebrating them, ignores the suffering of those who experience racism, and does not set children up to successfully identify racism and intervene.

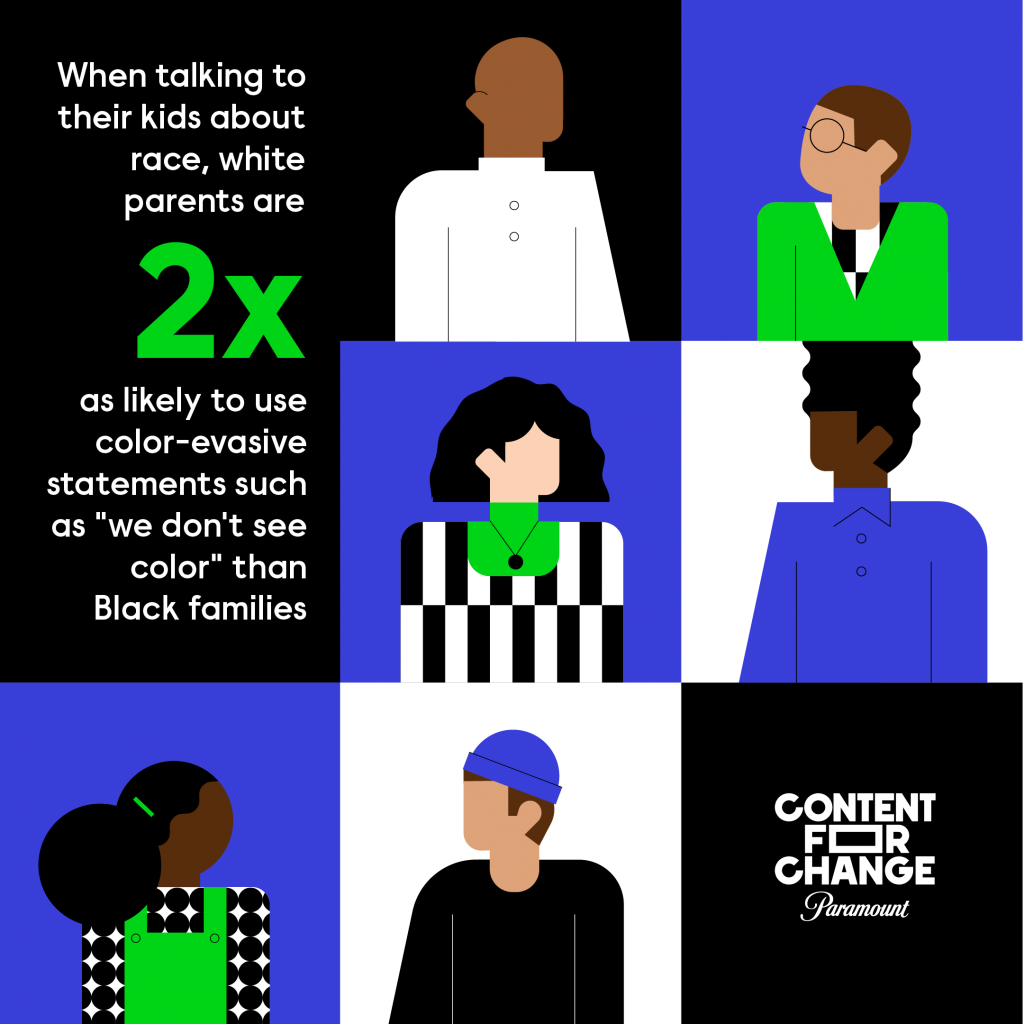

Though often well intentioned, White families are more likely to use "Color-Evasive" language.

The interviews with families were analyzed to understand the language that parents and children used. White families were more likely to use color evasive language (often referred to as “colorblind” language). These are statements such as "Race doesn't matter," "Color doesn't matter," or "We don't see race and color."

White kids used color evasive statements twice as often when discussing the scenarios compared to Black children and parents.

“That's kinda how I alway planned on teaching [my son] is like, it doesn't matter the skin color, everybody is the same.” - White mother

In the Parent interview portion, every single White parent used color evasive language, compared to only one-third of Black parents.

This approach can be problematic for several reasons. For example, it creates a taboo around race and differences; rather than celebrating them, it ignores the suffering of those who experience racism, and it does not set children up to successfully identify racism and intervene.

Black parents don't have the option to take this approach. They have to prepare their children for the reality of racism. When asked why they talk about race and racism with their kids, every Black parent mentioned needing to prepare their kids for the bias they knew they would face.

“I think it's important, especially because of things that happen in the world today. And you need to be honest with your kids and you need to let them know that this is real, people do behave like this.” - Black mother

The urgency and timeliness of having this talk for Black families was also something that White parents understood.

“They probably talk about it the minute their kids can start talking back, maybe even earlier. Just because they're the ones experiencing the racism so I feel like they need to prepare their kids for it as soon as they leave their houses for the first time even. You know? That the world isn't fair. It should be, but it isn't.” - White mother

Black parents were surprised by their children's responses to prompts.

Just because Black parents have experience with racism doesn’t make the conversation any easier. Half of Black parents were surprised by their child’s responses to the stories discussed. Black parents specifically mentioned wanting clarity around definitions of terms, age-specific guidance, and empowering resources.

“Even though she’s very smart, I hadn't figured out a way to explain to her for her six-year-old self to explain it and not be upset about it, and not be emotional about it.” - Black mother

White parents said their own lives and experiences have not prepared them to discuss race and racism.

Meanwhile, the majority of White parents say their parents never discussed race and racism with them, and are more likely to say that their child does not understand or notice race or racism. They often cite a lack of experience with racism and lack of racial diversity in their community as contributing to them feeling less prepared. Some White parents say they are shielding their children from the painful reality.

“As much as I want to talk about racial injustices with her, I think I’ve kind of sheltered her from it a little bit.” - White mother

White children expressed a lot of shock and confusion realizing, sometimes for the first time, that racism happens around them.

“Why would he do that? Because they’re the same kind of people just a different color. Why would that happen?” - White boy (age 8)

“This world’s so, like messed up. I don’t even know what to say.” - White boy (age 11)

White Boy (age 8): Why do they think Black people would steal the black one and the white people wouldn't steal the White one? It's weird, that's super weird to think.

White Mother: You see? All these things you never thought about, right? Because you don't have to worry about it because it doesn't happen to you. But it's true. I’ve seen it.

Kids think it will take a long time to achieve racial equality.

Kids were asked when they thought racial equality would happen. The majority of kids believe racial equality is one of the last challenges people will solve.

What do kids predict will happen BEFORE racial equality exists?

- Humans will travel to Mars

- Doctors will cure cancer

- The United States will have a female president

- We’ll experience climate change making Earth uninhabitable

Black children predicted racial equality would happen later than White, Asian, and Hispanic children did.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to our research study advisor board members: Dr. Allison Briscoe-Smith, Dr. Beverly Daniel Tatum, Dr. Rashmita Mistry, Nicole Stamp, Dr. Kira Banks, Dr. Riana Elyse Anderson, and Dr. Kevin Clark.

Thank you to the OK Play team and the Toronto Metropolitan University’s Children’s Media Lab for their collaboration on the “Talking to Families about Race & Racism” research project. And to the following individuals for their instrumental work on the research project: Dr. Remi Torres, Anna Kimura, Josanne Buchanan, Dr. Mamatha Chary, Maya Lennon, Adrianna Ruggiero, Amber Cape, Annika Daug, Eliza Rocco, and Maria Cruz Gutierrez.

Thank you to the Noggin and Nickelodeon teams who contributed to this work: Makeda Mays Green, Andrea Strauss, Ron Geraci, Dr. Michael Levine, Dr. Colleen Russo Johnson, Daniel Ramos, Angela Ojeda, Noelle Yoo, Brittany Sommer Katzin, Winnie Cheung, Courtney Wong Chin, and Hannah Peikes.

Thank you to Sparkler Learning for publishing the preschool-aged guide, “Discussing Race With Young Children: A Step-by-Step Activity Guide” that resulted from this work.