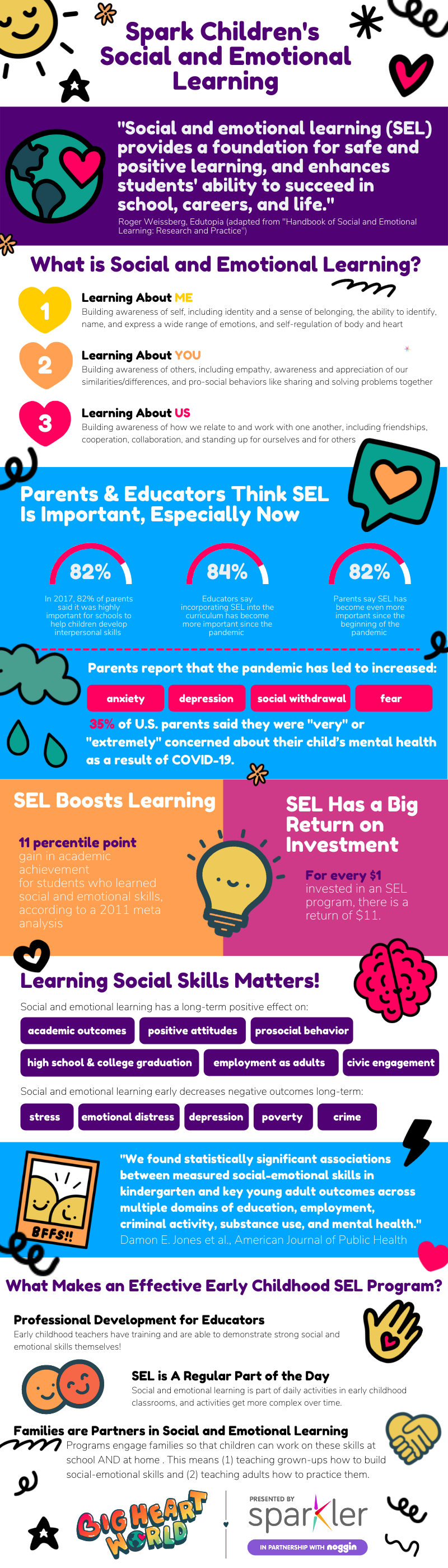

What is Social and Emotional Learning?

Two years into the pandemic, my second grader told me he’d like to plan a playdate with a friend from school. A minute later he asked, “But what do kids DO when they go over to each other’s apartments?” For us, pandemic life is now “normal” and the regular parts of growing up — from hugs to playdates — are not. And, as a parent, I join parents around the world wondering what the long-term impact of these years will be on my own children and how we can help kids bounce back from this time.

During the pandemic, children missed out on many parts of “normal” life. For most parents, the top worry is their children’s exposure to a broad group of skills called “social and emotional development.” Skipping two years of play dates, for example, has ME worried about my child’s ability to relate to others, work together, and solve problems as a team.

At the start of the 2021-22 school year, six in ten U.S. parents said their top concern for the coming school year is their child’s social and emotional wellness, about double the percentage of parents who voiced concerns about their children’s academic learning (source).

So, what is social and emotional development? Why does it matter? And how can educators and parents prioritize it right now? Learn more in our new infographic about social and emotional learning.

Sources

49th Annual PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools. Academic achievement isn’t the only mission: Americans overwhelmingly support investments in career preparation, personal skills. Kappan magazine supplement, PDK, September, 2017.

Clive Belfield, Brooks Bowden, Alli Klapp, Henry Levin, Robert Shand, Sabine Zander. The Economic Value of Social and Emotional Learning. Center for Benefit-Cost Studies in Education Teachers College, Columbia University, February, 2015.

Julie Cohen, Ngozi Onunaku, Steffanie Clothier, and Julie Poppe. Helping Young Children Succeed: Strategies to Promote Early Childhood Social and Emotional Development. Zero to Three, 2005.

Emma Dorn, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg. COVID-19 and education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning. McKinsey & Company, July 27, 2021.

Joseph Drulak, Roger Weissberg, Allison B. Dymincki and Rebecca Taylor, and Kriston B. Schellinger. The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: An Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child Development, January/February 2011.)

Susan D. Hillis et al. COVID-19-Associated Orphanhood and Caregiver Death in the United States. Pediatrics, December 1, 2021.

Damon E. Jones, Mark Greenberg, and Max Crowley. Early Social-Emotional Functioning and Public Health: The Relationship Between Kindergarten Social Competence and Future Wellness. American Journal of Public Health, October, 2015.

Stephanie M. Jones, Emily J. Doolittle et al. The Future of Children. Social and Emotional Learning. Princeton, Brookings, Volume 27, Number 1, Spring 2017.

McGraw Hill 2021 SEL Survey. 2021 Social and Emotional Learning Report. McGraw Hill, 2021.

Vivek H. Murthy, M.D., M.B.A. U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory: Protecting Youth Mental Health. December, 2021.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. Establishing a Level Foundation for Life: Mental Health Begins in Early Childhood: Working Paper 6. Updated Edition, 2008/2012.

Paul Terefenko. Q&A With Paul Tough: Environment Matters for Student Success. EducationWeek, June 30, 2016.

Roger Weissberg. Promoting the Social and Emotional Learning of Millions of School Children. Perspectives on Psychological Science, January 18, 2019.

Roger Weissberg. Why Social and Emotional Learning is Essential for Students. Edutopia, Feb. 15, 2016.